when do you start losing muscle mass and what should you do about it?

pause for a moment and imagine yourself, 85 years old, what are you doing? perhaps you’re playing with your grandkids and enjoying hobbies similar to what you do today, or maybe you’re living a slower life where you’re taking care of things around the house and making your usual trip to the grocery store for dinner supplies. whether you picture an active or slow life both share a common thread: independance. independence in your later years allows you to participate in your hobbies for as long as possible and not have to rely on other for simple tasks of daily living, like getting up from a chair or getting dressed. the best way to hold on to your independence?

exercise.

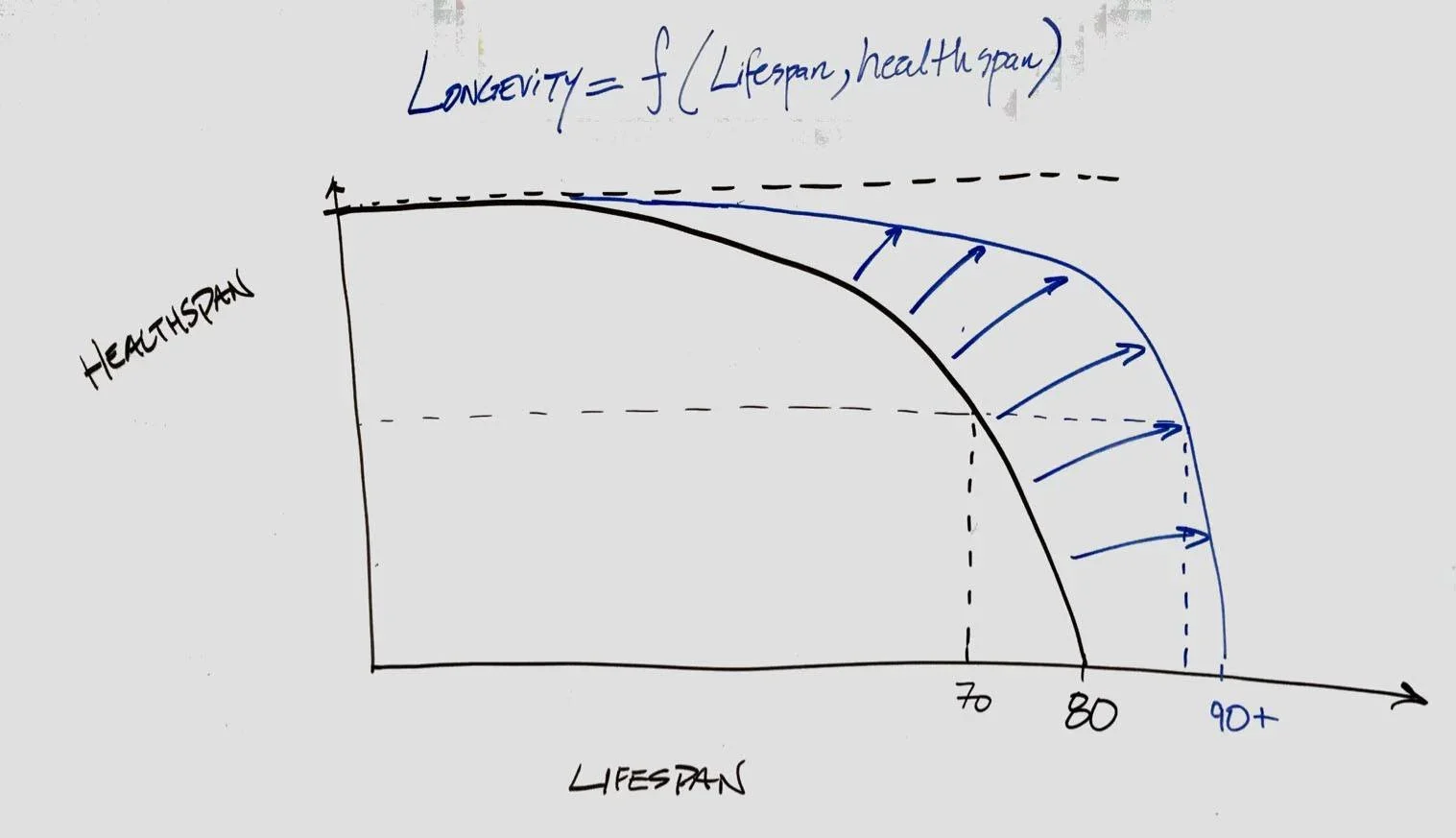

Aging is a complex topic with heaps of research, therapies, and debate swirling around it. what we know is that our biological clock is not perfectly synced up with our health clock meaning as we age we don’t automatically hold on to our ability to do daily activities we take for granted until our clock runs out. the graph below is a good visualization of this.

peter attia (peterattiamd.com)

when you look at this graph your age in chronological years is on the horizontal axis and your healthspan (or independence ability) is on the vertical axis. the black line is a normal trajectory of a person’s healthspan without adopting a lifestyle to improve this, you’ll see the line sharply decline around age 70. this signifies the time in everyone’s life where the rate of muscle mass loss, or sarcopenia, becomes accelerated. this acceleration in muscle mass loss is what makes it harder for people to perform tasks of daily living without assistance. fortunately or unfortunately a person may live 10, 20 or 30 years longer but spend these years fully reliant on others to help with daily tasks like standing up, getting dressed, or using the bathroom.

the blue line is a visualization of what can happen if you work on improving your healthspan. you can see the sharp decline around age 70 is much more gradual compared to the black line, and the sharp decline is pushed off to much later in life. this means if you work to improve your healthspan, you’ll be able to live independently longer because you can take care of yourself without assistance and thus experience a much greater quality of life during your later years. how can you do this?

exercise, let me explain.

as you age you lose muscle mass. with that loss in muscle mass you also lose strength and power. these are both very important for daily tasks like sitting and standing. so the weaker you are the harder it will be to do things you take for granted today when you are in your later years, things such as sitting down, standing up, getting up off the floor, and balancing on one leg to get changed. there are a few reasons you lose muscle mass with age but the main reason is that as you age your muscle fiber type changes. aging leads to an increased percentage of type i fibers compared to type ii. this decrease in type ii muscle fibers plays a large role in the age-related decline in strength and muscle mass. type i fibers are small, slow-contracting, low-tension output fibers with many mitochondria and aerobic enzymes for energy production (good for endurance bad for strength and power). type ii fibers are large, fast-contracting fibers that produce large tension output but fatigue quickly (good for low reps high output bad for slow sustained efforts). since type i fibers are smaller, contract slower, and become more numerous with age, you’ll experience a decline in muscle mass, strength, and power that you often won’t feel until at least your fifth decade of life.

why will you feel it only after your fifth decade of life?

it is generally agreed upon that your peak years for muscle mass development are between 24 and 34 years of age. this doesn’t mean you can’t build muscle at any age; it simply means this is the time where you’ll have the most capacity, and the easiest time, building mass and strength — so take advantage if you can. from there you’ll see roughly a 10% decline in mass and strength until you hit fifty years old. this decline is small enough that you probably won’t notice a difference. be aware of this false sense of security, because from 50 to 70 that rate of loss increases to about 10% per decade. from 70 onward it accelerates further to 25–40% per decade. that means by the time you hit 80 you could lose as much as 70% of your muscle mass compared to your mid thirties. this decline in muscle mass is accompanied by declines in strength and power, both of which are highly correlated with the ability to perform activities of daily living and prevent the onset of chronic disease.

fear not, the best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago, yes but, the second best time is today. muscle is fully capable of responding to resistance training no matter what age. for example, men over 66 years of age who trained by lifting 80% of their 1 rm (repetition maximum) for 12 weeks experienced strength gains of approximately 5% per day, similar to what is reported in far younger men. even more encouraging, adults over 90 years old have demonstrated strength improvements of up to 175%, as well as increases in the cross-sectional area of the thigh muscles by 15%, leading to meaningful improvements in functional mobility. it’s also not just strength that can improve at any age — aerobic endurance can also increase. adults between 60 and 80 years of age have experienced 20–30% increases in aerobic fitness with appropriate training, comparable to gains seen in much younger populations.

this is incredibly encouraging and highlights the importance of adding strength training into your routine regardless of age or background. to help guide your training, peter attia, an md who specializes in longevity, recommends four at-home tests with standards to aim for:

dead hang: 2+ minutes for men, 90+ seconds for women

farmers walk: carry your full bodyweight (or more) for 1 minute for men, and 75% of bodyweight (or more) for women

balance: hold a single-leg balance position for 30+ seconds for both men and women

getting off the floor: be able to get up from the floor using no hands, or one hand at most

if you can hit these targets excellent, try to go above and beyond them. if you can’t then that’s something to work towards in your training. now let’s discuss what you can focus on across various decades of your life in order to improve your healthspan and remain independent for as long as possible:

18–34: Build Peak Capacity

This is the period of greatest capacity for building muscle mass, maximal strength, power, bone density, and aerobic capacity. The goal is to create a high peak—because decline is inevitable, and you want to start from as high a level as possible. this is the time to invest more in peak muscle mass, strength and aerobic capacity. focus on strength across compound lifts (squat, hinge, upper push/pull, carry, lunge), make sure at least once a week you are adding in short bursts of power like pogo hops, box jumps, or sprints, and don’t ignore sustained low intensity efforts in your heart rate zone 2 (>150 min per week).

Aim to be above average or elite for your sex in:

Relative and absolute strength

Lean body mass with low fat mass

Power (e.g., jumps, throws, fast lifts)

VO₂ max

Example weekly structure:

Mon: Upper push / lower pull

Tue: 30 min run (Zone 2)

Wed: Upper pull / lower push

Thu: 20 min intervals (Zone 4–5)

Fri: Lunges / carries

Sat: 60 min long aerobic session (Zone 2–3)

Sun: Off

34–50: Maintain Strength, Protect Recovery

Strength and power remain the top priorities, but recovery becomes the limiting factor rather than motivation or capacity. the goal here is to sustain the strength and muscle mass you have, slowing the rate of decline as much as possible, and avoiding injury at all costs. it’s better to do a little less and not get hurt than to chase a new record and get hurt. an injury here will accelerate the rate of muscle loss and make it harder to recover.

Key adjustments:

Progress load more slowly (every 2–3 weeks rather than weekly)

Be more selective with volume and intensity

Maintain at least some power work (jumps, fast concentric lifts)

This phase is also ideal for expanding:

Low-intensity movement (walking, hiking)

Balance and mobility practices (yoga, tai chi)

Joint-friendly conditioning (cycling, rucking, rowing)

50–70+: Fight Sarcopenia Deliberately

Later-life training should focus on preserving muscle mass, strength, power, and independence. it’s important for this population ot not abandon heavier loads entirely. instead, lift “meaningfully heavy” with more total volume (more reps and/or sets), incorporate longer rest and recovery, and try not to train to failure. aim for moderate loads and instead of lifting a load for 4-6 reps, drop the weight and lift a load for 8-12+ reps. you can also utilize machines for added stability and safety ensuring you can keep the emphasis on eccentric control and full range of motion. because older adults experience age-related anabolic resistance —the reduced muscle-building response to protein and training— this means older adults need: More total resistance-training stimulus and Higher protein intake per meal. In addition to your time in the gym incorporate daily walking, low impact aerobic exercise (elliptical or bike) and keep some power work (even at low absolute loads) and grip strength in order to enhance your longevity and independence.

dietary requirements also change with age. common deficiencies include protein, vitamin d, and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, all of which have been linked to decreased muscle function. at younger ages, focus on eating enough total food rich in protein, fiber, and minerals to support muscle development and recovery. as you age, prioritizing highly digestible protein sources rich in essential amino acids may be helpful as muscle protein synthesis and breakdown rates change. however, more research is still needed to clearly define optimal diet and exercise strategies for successful aging.

when it comes to supplements, always consult with your doctor first. generally safe and well-supported options for increasing and maintaining muscle mass in healthy individuals include creatine and protein powder. for other supplements such as iron or vitamin d, it’s best to obtain blood work to identify any deficiencies before supplementing.

if you’re ever unsure where to start, reaching out to a qualified trainer can help ensure you’re following a plan that’s appropriate for your goals, age, and experience level, while performing exercises safely. building and maintaining muscle is one of the most powerful tools we have for longevity, independence, and quality of life.

to health!

miles is a trainer, speaker, writer, and consultant who specializes in performance and longevity within the health and wellness space. with over ten years of experience, a masters degree in exercise and nutrition science and multiple strength and conditioning certifications miles aims to combine practical application with research to provide actionable strategies for people looking to live longer and excel athletically.

References

Siparsky PN, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE Jr. Muscle changes in aging: understanding sarcopenia. Sports Health. 2014 Jan;6(1):36-40. doi: 10.1177/1941738113502296. PMID: 24427440; PMCID: PMC3874224.

Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt M, Schwartz AV, Simonsick EM, Tylavsky FA, Visser M, Newman AB. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006 Oct;61(10):1059-64. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1059. PMID: 17077199.

Hughes VA, Frontera WR, Wood M, Evans WJ, Dallal GE, Roubenoff R, Fiatarone Singh MA. Longitudinal muscle strength changes in older adults: influence of muscle mass, physical activity, and health. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001 May;56(5):B209-17. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.5.b209. PMID: 11320101.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2015.06.009

Larsson L, Karlsson J. Isometric and dynamic endurance as a function of age and skeletal muscle characteristics. Acta Physiol Scand. 1978 Oct;104(2):129-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06259.x. PMID: 152565.

Abellan van Kan G, Cderbaum JM, Cesari M, Dahinden P, Fariello RG, Fielding RA, Goodpaster BH, Hettwer S, Isaac M, Laurent D, Morley JE, Pahor M, Rooks D, Roubenoff R, Rutkove SB, Shaheen A, Vamvakas S, Vrijbloed JW, Vellas B. Sarcopenia: biomarkers and imaging (International Conference on Sarcopenia research). J Nutr Health Aging. 2011 Dec;15(10):834-46. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0365-1. PMID: 22159770.

Heath GW, Hagberg JM, Ehsani AA, Holloszy JO. A physiological comparison of young and older endurance athletes. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1981 Sep;51(3):634-40. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.51.3.634. PMID: 7327965.

Seals DR, Hagberg JM, Hurley BF, Ehsani AA, Holloszy JO. Endurance training in older men and women. I. Cardiovascular responses to exercise. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1984 Oct;57(4):1024-9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.4.1024. PMID: 6501023.

Frontera WR, Meredith CN, O'Reilly KP, Knuttgen HG, Evans WJ. Strength conditioning in older men: skeletal muscle hypertrophy and improved function. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1988 Mar;64(3):1038-44. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.3.1038. PMID: 3366726.

Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, Meredith CN, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ. High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians. Effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA. 1990 Jun 13;263(22):3029-34. PMID: 2342214.

Candow DG, Forbes SC, Little JP, Cornish SM, Pinkoski C, Chilibeck PD. Effect of nutritional interventions and resistance exercise on aging muscle mass and strength. Biogerontology. 2012 Aug;13(4):345-58. doi: 10.1007/s10522-012-9385-4. Epub 2012 Jun 9. PMID: 22684187.

Millward DJ. Nutrition and sarcopenia: evidence for an interaction. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012 Nov;71(4):566-75. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000201. Epub 2012 Mar 19. PMID: 22429879.

Robinson S, Cooper C, Aihie Sayer A. Nutrition and sarcopenia: a review of the evidence and implications for preventive strategies. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:510801. doi: 10.1155/2012/510801. Epub 2012 Mar 15. PMID: 22506112; PMCID: PMC3312288.